The history of the draped garment dates back to 3500 BCE. Across the land, visual arts of ancient sculptures, terracottas, cave paintings, and wood carvings depict men and women in unstitched cloth with various draping styles.

A notable draped garment in the East is that of the Buddha, called the kāṣāya, named after ochre, an earthy pigment containing hematite that varies from light yellow to brown and red. Original kāṣāya were made with old, recycled fabric, then dyed through boiling with vegetable matters, such as gleaned roots and tubers, plants, bark, leaves, flowers, or fruits, to achieve the ochre tone. The kāṣāya is then constructed from 3 pieces of cloth – the antarvāsa, the uttarāsaṅga, and the saṃghāti. Together they form the “triple robe,” or ticīvara. The antarvāsa is the undergarment. Essentially a wide skirt, it hangs above the ankles. The uttarāsaṅga is a robe that comes over the undergarment, the antarvāsa. In representations of the Buddha, the uttarāsaṅga is often covered by the saṃghāti. The saṃghāti is the outer cloak. Influenced by Alexander The Great’s brief invasion into the northwestern fringe of the Indian subcontinent, the Gandhara art depicted the shape and folds of the saṃghāti in the style of the Greek himation.

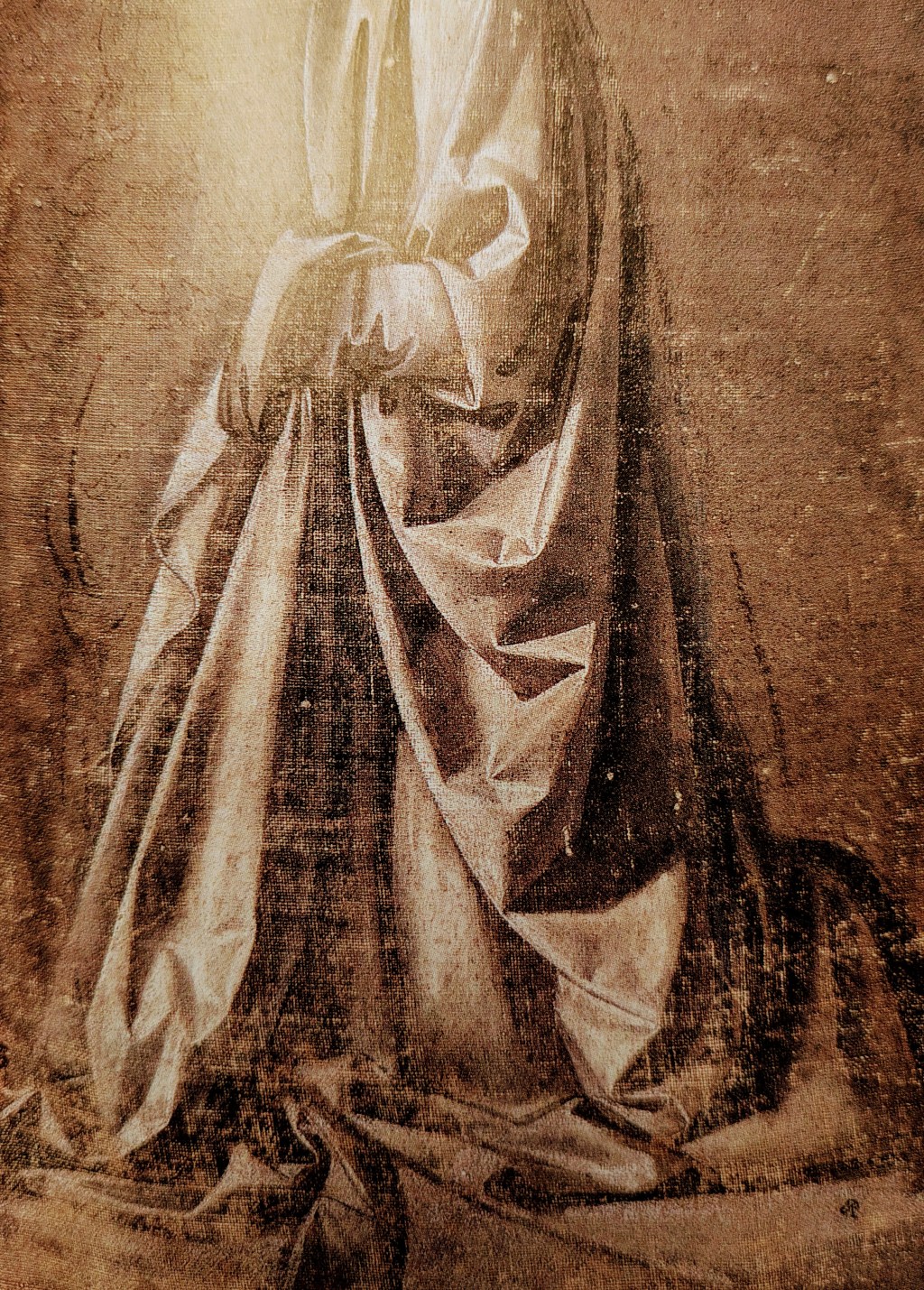

In the West, Leonardo DaVinci left behind a collection of drapery studies. The biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote that in order to execute the study, DaVinci “made clay models, draping the figures with rags dipped in plaster, and then drawing them painstakingly on fine Rheims cloth or prepared linen,” which meant they could not be worked using the usual materials of crayons or pen, but only with a brush. As the linen was first evenly coated with a brown or grey preparation, the draughtsman had to work from dark to light. After laying down the outlines and areas of shadow in black, the study would be built up in lighter shades and completed with white heightening. The drapery studies reveal the fascinating play between light and shadow upon the folds of the draped garment.

By standard, clothing is categorized as either “fitted” or “draped.” A “fitted” garment is sewn together and worn close to the body, in contrast to a “draped” garment that doesn’t require sewing. The creative advantage comes through during the draping process as interesting designs take shape. An exemplification of this creativity expression is Madame Grès, who polished and perfected the Grecian gown, her emblem for nearly two-thirds of the 20th century. With her sculptural background, Grès began with three dimensions, circling and swiveling the drapery around the real body. Because she created her toile three-dimensionally, she could observe, maneuver, and manipulate the cloth before making any decision. She realized her forms through the direct action of the cloth, be it billowing taffetas or flowing silk crepes. Grès respected the cloth as a whole, always preferring not to cut. Thus, the structural integrity of the drapés resided in their unbroken panels of fabric. Her sensual purity is akin to the sculptor Antonio Canova’s ideal of supple and voluptuous classicism and the painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s evocation of the tremulous, yet still, beauty of liquid line. Her drapé owed its mystery to the elements of voluptuous excitability, pensive sensuality, and repressed eroticism. It’s a perfect neoclassicism.*

In his essay, Lumbar Thought, Umberto Eco mused about how dress as armor has influenced behavior and in consequence, exterior morality, in the history of civilization. “The Victorian bourgeois was stiff and formal because of stiff collars; the nineteenth-century gentleman was constrained by his tight redingotes, boots, and top hats that didn’t allow brusque movements of the head. If Vienna had been on the equator and its bourgeoisie had gone around in Bermuda shorts, would Freud have described the same neurotic symptoms, the same Oedipal triangles?” Eco then argued that thinkers, over the centuries, had fought to free themselves of armor. The monks had invented the robe that, while fulfilling the requirements of demeanor, left the body free and unaware of itself. Monks were rich in interior life and very dirty, because the body, protected by a habit that ennobled it, released it, was free to think, and to forget about itself. Thought abhors tights.

*Richard Martin & Harold Koda. Exhibition “Madame Grès”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 13 – November 27, 1994.