Mashed fruits, left alone for some time, ferment themselves. Natural yeast already present in their juices consume readily available sugar to make alcohol and gas. Grains, unlike fruit juices however, lock their sugars in starches. In order to ferment grains, their starch chains need to be unpacked and then digested into sugars by enzymes. The choice of enzymes can be as wild as human saliva. In the Amazonian rainforest of Peru, locals chew yuca and ferment the masticated and spat out root into the alcoholic beverage called masato de yuca. Beer is made by moistening a portion of raw grains, called malting, so that they begin to sprout and generate enzymes to turn their own starch into sugar. In East Asia, rice is inoculated with mold and yeast to unlock sugar and digest it into alcohol at the same time, known as a parallel fermentation process.

The most delicate of all rice wines is sake, a Japanese variety refined in temples in the twelfth century and then streamlined in the twentieth. To make sake, rice is polished to remove the outer layers – which contain vitamins, fats, and proteins – in order to arrive at the “heart” of the rice grain, which is the starch. Instead of a complex wild starter, the mold of choice is Aspergillus Oryzae, the koji, and only specific strains of yeast are selected for their brewing qualities. Of the many types of sake, junmai is made from only koji, rice, water, and yeast. Junmai ginjo and daiginjo are defined by the mass of rice being milled. A minimum of 40% of the original grain mass must be polished away to be classified as ginjo sake, and a minimum of 50% for daiginjo sake. More polishing results in smoother, lighter, and cleaner tasting sake. Ginjo expresses fruity and floral characteristics, while junmai carries earthy, smoky, and rice-eccentric aromas.

To make my rice wine, I followed the sake method, using koji and yeast for fermentation. However, I chose to use sweet rice instead of polished rice. Sweet rice, unlike the japonica or indica variety, contains negligible amylose but high quantity of amylopectin starch, which is particularly good at retaining moisture when cooked in hot water or steamed. Over 6000 varieties of sweet rice originate from South East Asia, but the sweet rice “collector’s paradise” is Laos, claiming an estimated 85% of the country’s rice production. Requiring less water, it is grown in both wet lowland and hillside upland paddies. 3200 varieties of sweet rice come from Laos alone. I also chose to use a wine yeast because I found it was not easy to purchase a sake-specific yeast strain.

The first step is to use a third of the sweet rice to grow rice koji, which takes about a week. The sweet rice needs to be soaked overnight, then steamed until tender. Once cooled, mold spore is sprinkled atop, and it can be kept covered in the oven. Leave the oven light turned on for a couple of hours daily to keep it warm. Once the rice koji is fully grown, steam another third of the rice and mix this steamed and cooled rice with half of the rice koji, water, and a packet of yeast in a sanitized vessel. The typical ratio for sake is 1 gallon of water for 6 lbs of rice. So for this first stage of fermentation, only half of the amount of water should be used. Refrigerate the other half of rice koji until the second addition. Keep lidded and within a few days, the yeast should be fully active and bubbles should float atop the rice mash. After a week to ensure that both koji and yeast are healthy and happy, steam and cool the remaining third of the rice to add to the mash along with the rest of the koji rice and the remaining half of the water. It depends on the environmental temperature to determine how long fermentation should last. Preferably brewed in the cold winter, temperature between 45F and 65F, it can take as long as 4-5 weeks. I kept mine in the food pantry and let it ferment for 2 more weeks, bringing the total fermentation time to 3 weeks.

Once fermentation completes, it can be racked off into smaller vessels. Unlike fruit wines, it is fairly difficult to rid the rice slurry completely in order to have a clear sake. Refrigeration to settle the lees and multiple racking may be required. I ended up using a Greek yogurt strainer to further clarify after the first rack. Even after that, pour ever so gently so as to not disturb again the lees settling at the bottom.

Because there is no original sugar available to be measured like fruit wines, computing the alcohol content for sake is more complicated. First, the specific gravity of the sake is measured. Then it needs to be evaporated to half the volume. To evaporate to 125 ml, I heated 250 ml of sake in a heat resistant glass measuring cup at 400F for ~60 minutes. Then it is refilled to the original volume of 250 ml with water, and its specific gravity is measured again. Compute the spirit indication: SI = (SG2 – SG1)*1000; then, the formula for alcohol percentage is:

%ABV = (0.008032927443 * SI2) + (0.6398537044 * SI) – 0.001184667159.

My resulting measurements were SG2 = 1.03, SG1 = 1.01, and %ABV = 14.12%, a typical alcohol percentage also for fruit wine.

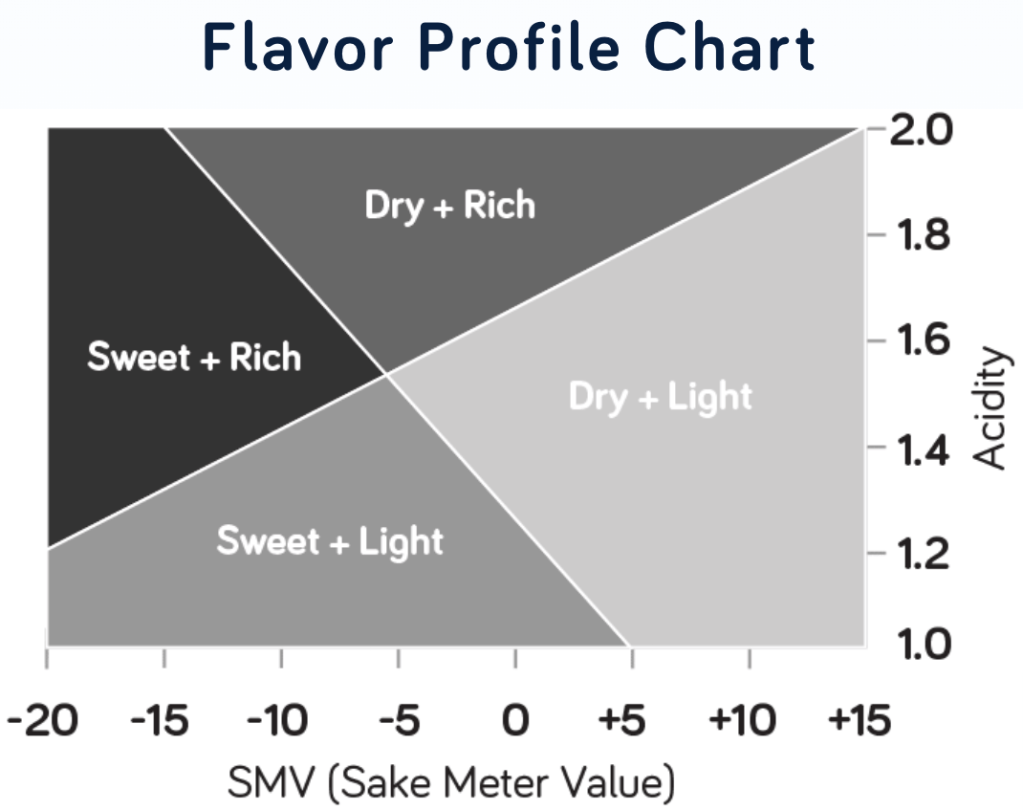

Sake evaluation looks at two metrics: Nihonshu-do, the sake meter value, and its acidity level. SMV measures the sugar content and gives insight into the sake’s sweetness in taste. Acidity level refers to its acid content: a higher value signals higher acidity. Acidity balances out the sweetness and gives a richer body. Both metrics can be computed based on specific gravity and pH measurements. To compute SMV: SMV = (1÷SG1 – 1)*1443 → SMV = -16.5.

To compute acidity level: pH = -log (x÷100).

For my measurement: pH = 4.4 = -log(H+) → H+ = 0.0122773 → Acidity level = 1.22773. The typical acidity level for sake is between 1 and 2. Both SMV and acidity level combined suggest its flavor profile. A sake with SMV of -16.5 and acidity level of 1.2 is considered sweet and light.

After a month, my rice wine smells floral and fruity, with a faint mushroom note. Not heady, but its aroma profile suggests that of a light and sweet cherry blossom. Its hue is of light yellow grass. It tastes smooth and sweet, with a velvety mouthfeel and a medium finish. A typically dry junmai smells cheesy and umami-like with SMV ranging in the higher positive values. A SMV for a junmai ginjo ranges in the lower negative values, but with a higher acidity level to balance out the sweetness in order to pair well with food. Overall, with its sweetness and floral characteristics, this wine drinks well on its own. The floral qualities of rice wine come forward especially when drunk unpasteurized. However, it can be pasteurized and also aged, though most is aged for only 6 months and consumed within a year.