I once met a girl who spoke four languages. I asked her how she kept them all straight in her head. Smoke puffing out from her lips, she admitted that it was getting very full, and that she didn’t think she could hold any more words in there. I told her that I didn’t know how people could even learn four languages. Eventually, I figured out that if one spoke two languages, such as English and Spanish, picking up another Romance language like French would only take a fraction of the labor. If one spoke Spanish, it would take a small effort to understand Italian or Portuguese. Then I met a French girl who also spoke English, Spanish, and Chinese. Chinese is not a Romance language and is of a completely different makeup. But I didn’t ask her how she kept them all straight in her head; it works in mysterious ways.

Well, I’m bilingual and it feels like my head is already stuffed at times. It’s assumed that being bilingual means one can speak either language fluently simultaneously, but this does not apply to me. For most of the vocabulary most of the time, English is my primary language, meaning that I first think of words in English. Since my daily communication is in English, this is obvious. Yet for certain pockets, Vietnamese is the primary language. Very weirdly, I think of numbers in Vietnamese. For example, memorizing a string of numbers is most easily done in Vietnamese. However, it takes more work to find the Vietnamese equivalence for other words, often requiring the aid of a dictionary for complex vocabulary. Most dreaming is done in English, but a dream in Vietnamese sneaks in once in a while. It’s usually a pleasant surprise, leaving me wondering how it came about suddenly.

Some years ago, I listened to a piece arguing against the assumption that people could multitask. It proposed that our brain was only switching between tasks sequentially but quickly, thus giving the impression of multitasking. It would explain why the greater number of tasks we try to manage at a time, the more poorly we perform at each of them, and even more acutely so for complex ones. It would also explain why my brain does not simultaneously access both languages at a time. Since I do not speak Vietnamese daily, it takes a considerable amount of time to switch to it, thus does not give the impression that I can multitask in languages. Being slow is commonly understood as being dull-witted, but there is a distinction between the two. Given time, a slow mind eventually retrieves information, but no amount of time can bring about anything from an empty head.

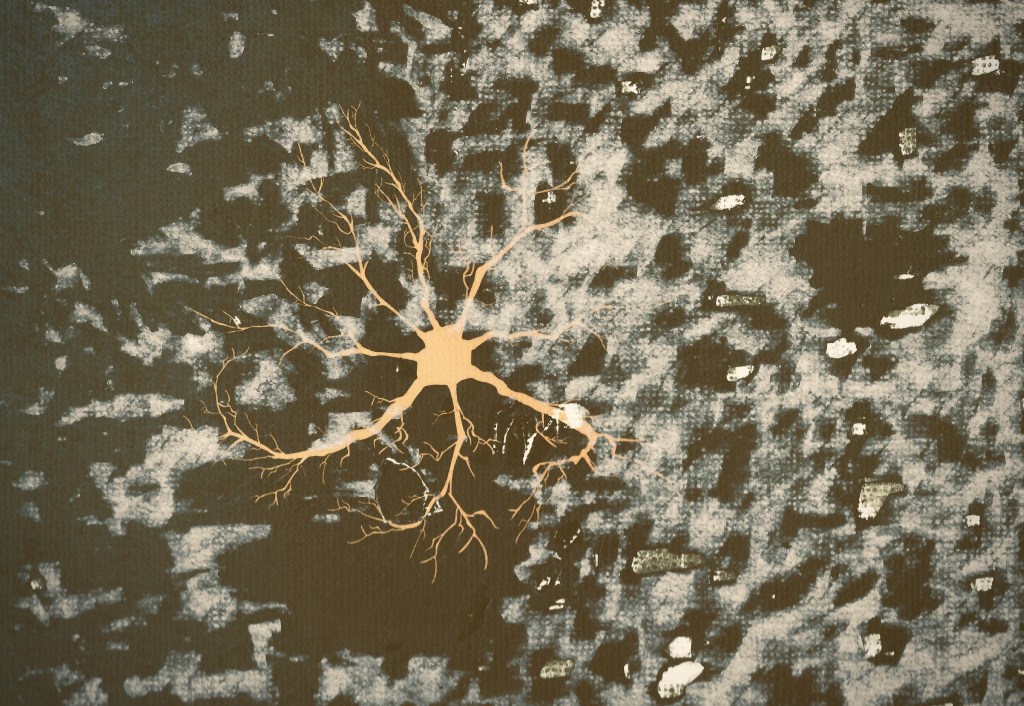

When we attempt to compare our brain to a computer, we should do so with a sense of humor. Just about a couple of hundred years ago, people likened the brain to a mechanical system made of clocks and gears. We humans have the habit of analogizing our mind to our latest invented technologies. And we do so because it helps us make sense of the most mysterious working system that we supposedly possess. Whereas the computer’s inputs and outputs are comparable to our body parts, the brain’s physical makeups are not comparable to a computer’s components. Rather we think of it in terms of functions and performances. The computer’s central processing unit, the CPU, is the time keeper, and its memory storage can be viewed as a collection of information cells. For a complex system, most essential are the pathways connecting the information cells to the rest of the system. Data for fast access are stored in cache, and long-term memories in a hard disk. Likewise, immediate information required for daily function needs to be in front, while others are somewhere in the back of our mind. It takes time to get to long-term memories, depending on how fast our CPU is and the pathway’s mapping, which is rewired whenever we access an information cell.

To find an English word’s equivalence in Vietnamese, my brain may need to travel back to long-term memories. Depending on its complexity and usage frequency, the pathway may be long and winding. How does it know that the word it’s pulling is correct? -It does not know for sure. My experiences of reading, writing, speaking, and hearing the word in actions have the greatest weight in validating the word of choice. The less experiences, or the less information linked to the word is available, the more likely the output is incorrect. Additionally, there are other words with similar meanings. In the end, it chooses one with the highest chance of being appropriate for the specific context. Fortunately, once the word of choice is validated as appropriate for the context, the pathway is rewired and renewed. If I muse over it for some time, it may even get a front seat. Headspace is prime real estate; I must choose wisely.

It is reasonable to argue that if we can describe a function in the computer’s language, then the computer has the odds to outperform us at it. Language translation is one of these functions. You only need to use one of the free online translation applications to see how good it already is at translating between English, French, and Spanish. And the more data in any language is uploaded onto the internet, the better it gets. There is ever more storage capacity for information, and processors are fast converging toward Huang’s law. But when our brain holds multiple languages, it synthesizes information into knowledge and wisdom. How do we describe knowledge and wisdom to a computer?

Just as how do we describe creativity? How do we describe sacrifice, altruism, or love, or the vast range of emotions and feelings that have evolved and flourished across cultures for millennia?