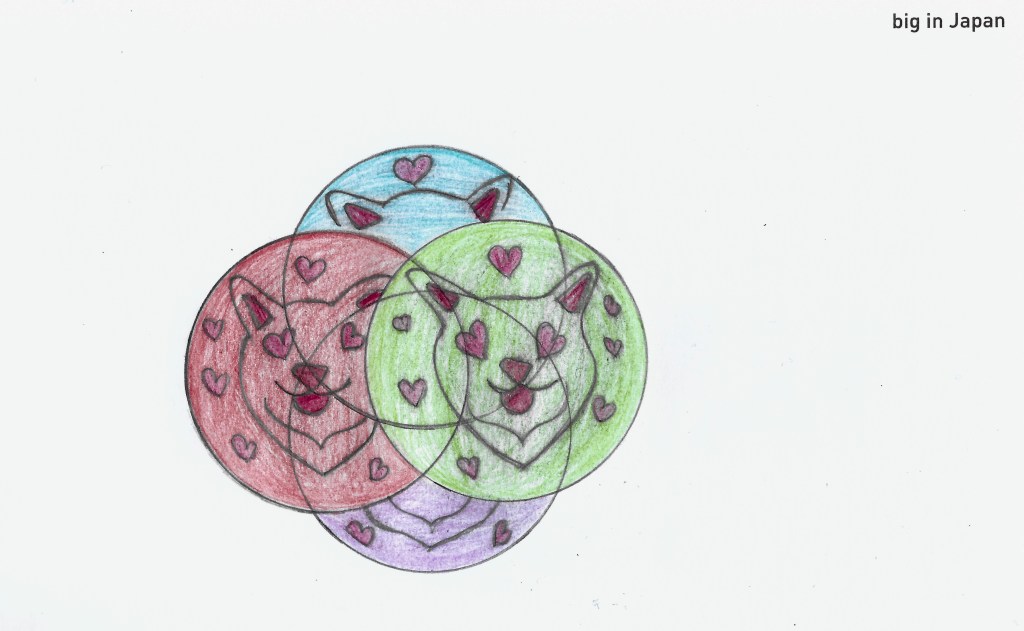

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the Japanese concept ikigai as “a motivating force; something or someone that gives a person a sense of purpose or a reason for living”. It is to give meaning to life, a raison d’être. Here, we have furthered it into a venn diagram consisting of four circles: what the world needs, what you can be paid for, what you’re good at, and what you love. From these, four more concepts are defined. Your vocation is what the world needs and what you can be paid for. Your profession is what you can be paid for and what you’re good at. Your passion is what you’re good at and what you love. Your mission is what you love and what the world needs. And finally, the sweet spot, which is the overlapping of all four circles, is your ikigai.

The idea that workplace happiness can be achieved by following your passion began in 1970 by Richard Bolles, an Episcopal priest from San Francisco. A radical concept of that time, it would be accepted as conventional wisdom over the next 40 years. Within the last decade, however, scholars have casted doubts upon its validity. Among them is Cal Newport, who wrote numerously to debunk this myth. He called it the passion trap, arguing that the reality was actually the opposite. The more emphasis is placed on finding work you love, the more you become unhappy when you don’t love every minute of the work you have.

Central to the argument is that passion does not come first, but is cultivated. Conventional wisdom tells us to figure out what we love, then to find work to match it. But worthy subjects take years to master, through deep focus and hard work. And deep focus does not come naturally; it takes determination and grit. I would argue that what we need to cultivate is the ability to overcome the discomfort of having to focus on a hard subject for a long time, which is becoming more challenging in this modern age of the internet. Upon mastering what we’ve been toiling for, we come to appreciate it, to take pride in it, and to love it.

Along this vein of thought, I propose that we revisit our idea of a dream job. If finding a passion is hard, the challenge to finding a dream job would be manifold. Cultivating a passion is largely dependent upon our own effort, but the chase to a dream job is compounded by numerous external factors, not excluding random chances. The immediate factor is whether a living wage can be earned from a chosen field at a certain skill level. Some professions pay well for a range of skill levels, whereas others make liveable wages only at the top end of the spectrum. If extra skill sets are needed in order to work in our chosen field, then we must acquire them regardless of our affections for these supplemental subjects. At times, one may unfortunately find that they hate something more than they love a thing. Then of course, there is the human challenge, for a job necessitates that we work with others, and few are motivated to help us realize our dream job.

Take the field of cookery as an example. At the low end of the skill spectrum, it pays minimum wages. After years of toiling, one may become a chef, at which point there are generally two options. They may choose to pursue their own endeavor, such as opening a restaurant. But running a restaurant is more about running a business, and less about cooking. Do they love running a business? If not, they may choose to become head chef at someone else’s restaurant. But to cook for a boss comes with its own challenges, some of which may be hard to stomach. At every level, the advancement of their career is affected by those they interact with. Only the very few who are extremely good and extremely lucky go on to become the celebrity chefs that we revere.

Thus I would also propose that we take pride in our vocation. To be able to provide what the world needs and make a living wage from it is a benchmark of adulthood, of maturity. We are confident when we can be independent; we earn self-esteem when we are useful and helpful to others. If there is an opportunity to evolve the vocation into a profession, then by all means we should cultivate it. However, we should take care to not allow the daily tedium of the job to take away the joy of doing what we love. Take writing as an example. What you want to write often has little in common with what a job asks you to write. While the act of writing anything improves your craft, do not let the job drain away any spark for that which you actually love to write.

Aside from our vocation, we should make every effort to cultivate a passion. The time we take to pursue what we love is not in vain, for it gives back the energy and excitement that the job may have depleted from life. And when one becomes so good that they cannot be ignored, they may just be able to turn it into a full-fledged profession, live their mission, and reach ikigai.