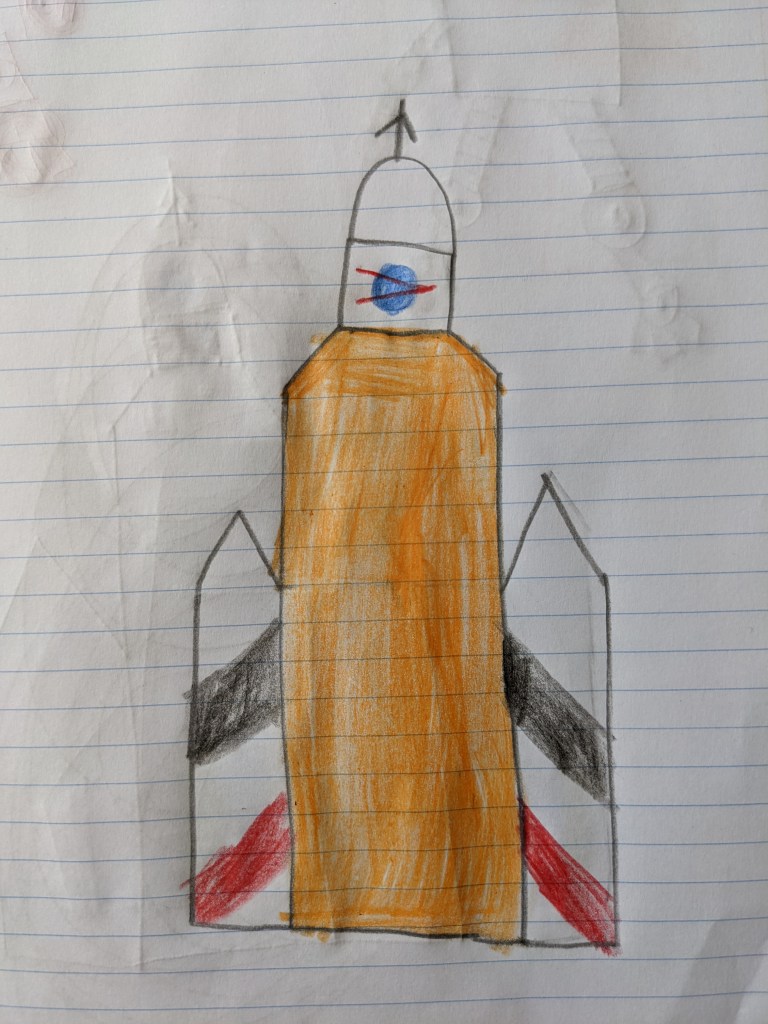

I had composed a list of spaceflight animations for my kid since he was a toddler. They mostly run at ~5 minutes, but his favorite was the longest one, depicting the Space Launch System’s exploration missions to the Moon and to Mars.

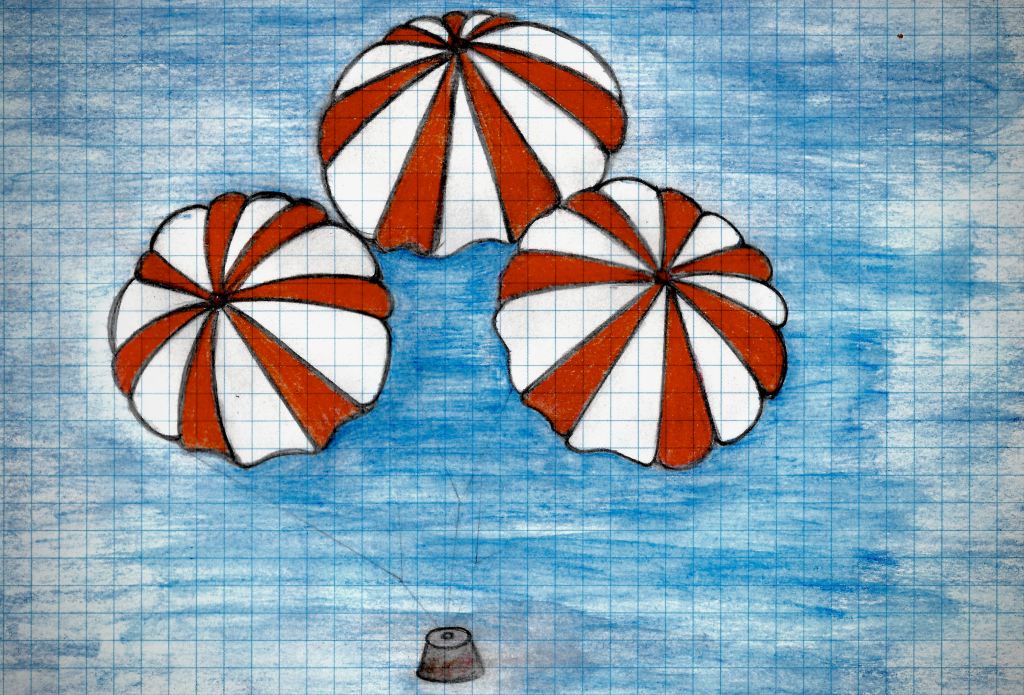

Recently, all the excitements around the launch of Artemis-1 got him interested in spaceflights again. He spent his weekends rewatching the SLS and drawing it. Once, he took three orange balloons and tied a little LEGO figurine onto them. He then proceeded upstairs to drop the balloons along with his action figure. I recalled the parachuting scene at minute 12:40 and thought it was a rather witty representation of the orange parachutes in the animation.

Balloons are not parachutes, but they use the same physics principle, which is to take advantage of air resistance, to slow the fall. Without the presence of air, everything falls under earth’s gravity with the same acceleration g = 9.81 m/s². However, by altering their shapes and densities, the resistance from the air surrounding the objects can keep them floating for longer.

Over 2000 years ago, Archimedes of Syracuse discovered that the buoyant force on an object was equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. For a gas-filled balloon, gravity pulls down on the balloon while the air pushes up with a force equal to the weight of the air that the gas displaced.

We decided to run a little experiment to help our hero, whom he had affectionately named Gru, land safely. First we dropped Gru himself from the top of the staircase. He hit the bottom at .9 second, his helmet ejecting itself from his head, deadly if Gru were a real person. Then we tied him to three balloons, filled with our own breaths. This time, Gru landed at 2.2 seconds, already much more slowly than originally.

But we could get Gru to land even more slowly if the balloons were filled with a lighter gas, such as helium. If the minimum falling time is 4 seconds in order to land safely, how many helium-filled balloons are required and how large for each balloon? To answer these questions, several physics formulas are utilized.

** The kinematics:

[vt = vo + at] AND [h = (vt + vo)t÷2] AND [vo = 0 m/s] → a = 2h÷t²

Knowing the required falling time, t, and the staircase’s height, h, which is the distance from the dropping point to the floor, we can compute acceleration, a. In our use case, h = 3.89m and t = 4s → a = .49 m/s².

** Archimedes’ principle states that Fbuoyant = gρVf = gmf →

Fbuoyant = Fnet = g(mGru+mBalloons+mGas-mAir)

** Newton’s 2nd law of motion states that F = ma →

Fnet = (mGru+mBalloons+mGas)a = g(mGru+mBalloons+mGas-mAir)

(mGru+mBalloons+mGas)a = g(mGru+mBalloons+mGas-mGasρAir÷ρGas)

In order to compute the helium mass required, we need to know the mass of the balloons. Assuming that we will use 3 balloons, the total balloon mass is 3 times the mass of each balloon. Each balloon and string weigh 1.5 grams, thus the total balloon mass is 4.5 grams. Knowing the following constants:

. Gru weighs 3 grams

. Gravitational acceleration g = 9.81 m/s²

. Air’s average density ρAir = 1.225 kg/m³

. Helium’s average density ρHe = .1785 kg/m³

→ mHe for 3 balloons = .00121 kg → mHe for each balloon = 0.0004 kg.

Vsphere = 4πr³÷3 → rHe is .046 m

→ To land Gru at 4 seconds, it requires 3 helium-filled balloons and the diameter required for each balloon is 9.2 cm.

In our experiment, using 3 helium balloons, Gru landed at 4.7 seconds. In a perfectly controlled lab environment, the physics should come out perfect, and computed values should match expectation. In our house, we used a kitchen scale which was only accurate to the gram. Because we dropped Gru from upstairs, sometimes he landed on a stair step next to the floor instead. Combined with the operators’ precision errors, such as aligning the timer to the drop and landing time, our experiment was indeed not within a controlled environment.

But neither is the real world. That’s where engineering comes in. Engineering is applied science. We assess error margins, compute ranges of acceptable values, and where necessary, test, test, and test again. Because we all want our hero to land safely.